What a year 2020 had been. Reflecting on the build-up to my diagnosis through the year – the aspiration pneumonia, the onset of weakness in my arms, difficulties with speech and swallowing… I came to realise that I’d actually been focusing on the wrong things for many years.

In 2003 I’d had the first of two heart attacks at the age of only 48. Just six years later I was diagnosed with prostate cancer. In the first ten or so years of the new century I’d had several angiograms, two sets of stents in coronary arteries, and a robotic radical prostatectomy to sort out the cancer.

So I was ultra-cautious. I was careful not to over exert myself or to get too stressed. Either could have had consequences for my chronic coronary artery disease. I was also watchful for other symptoms that may have been associated with the cancer. I was really fortunate enough to be able to retire early, to change my lifestyle, to travel, to relax, and to enjoy time together with Sue.

Little did I know that I’d hit the jackpot and would go on to develop a third fatal disease! My eyes had been on the wrong ball and I guess the earliest symptoms of MND had passed me by as minor inconveniences.

More than this, after our traumatic experience in Vietnam – the awful COVID quarantine hospital, the pneumonia and the dash to get home on the last flight before lockdown, that illness really was high in my consciousness and it got the blame for a number of the subsequent MND symptoms. My voice sounding hoarse, increasing tiredness, another chest infection etc.

But I also reflected on how lucky I had been. Some people sadly are passed from pillar to post, from consultant to consultant, trying to diagnose their MND over many stressful and frustrating months. Thinking about it, the first real indications that I had something seriously wrong with me were at the beginning of August 2020 and just days later my GP had referred me to a neurologist. In early September I was told that all the symptoms sadly pointed to MND. Four weeks later that was fully confirmed. The fact that this speedy process of diagnosis happened during the COVID pandemic makes it all the more remarkable.

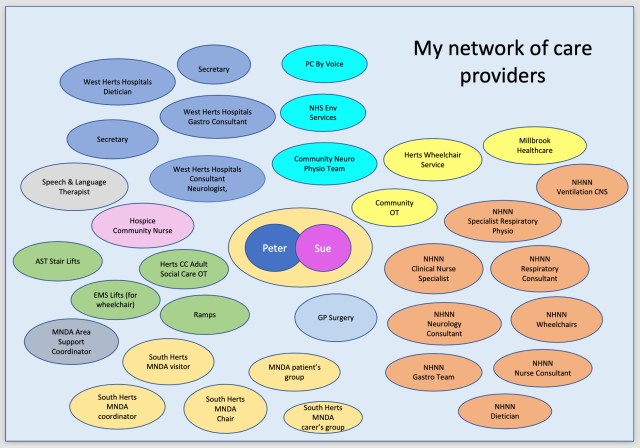

I’ve also been very lucky to have been referred on to ‘The National’ (Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery) at Queen Square in London, just 35 minutes from home by train and a world class centre of excellence with the most supportive and co-ordinated clinical team one could ever hope to come across. And it’s all free of any costs under the NHS. Amazing.